Optimal posture isn't just about looking confident; it's the foundation of your body's ability to distribute weight evenly, minimize mechanical strain, and function efficiently. Achieving and maintaining the spine's natural, balanced curves—often called the "S-shape"—is critical for overall health and long-term well-being. This guide delves into the science of posture, exploring its biomechanics, common causes of dysfunction in our digital age, and evidence-based strategies for correction and prevention.

I. Foundations of Optimal Posture: Biomechanics and Assessment

Understanding the principles of ideal alignment is the first step toward achieving it.

I.A. Defining the Neutral Spine: Static Alignment Criteria

The neutral spine represents the ideal static alignment, minimizing load and maximizing stability.

Standing Alignment

In an optimal standing posture:

- Weight is evenly distributed across the arch of the foot.

- Hips are neutral, and the rib cage is gently tucked down.

- The spine maintains its natural S-curve (avoid excessive hunching or arching).

- Shoulders are drawn down and back.

- The head is centered precisely over the shoulders, with the chin tucked (neutral position) and eyes forward.

- Knees are kept soft (not locked).

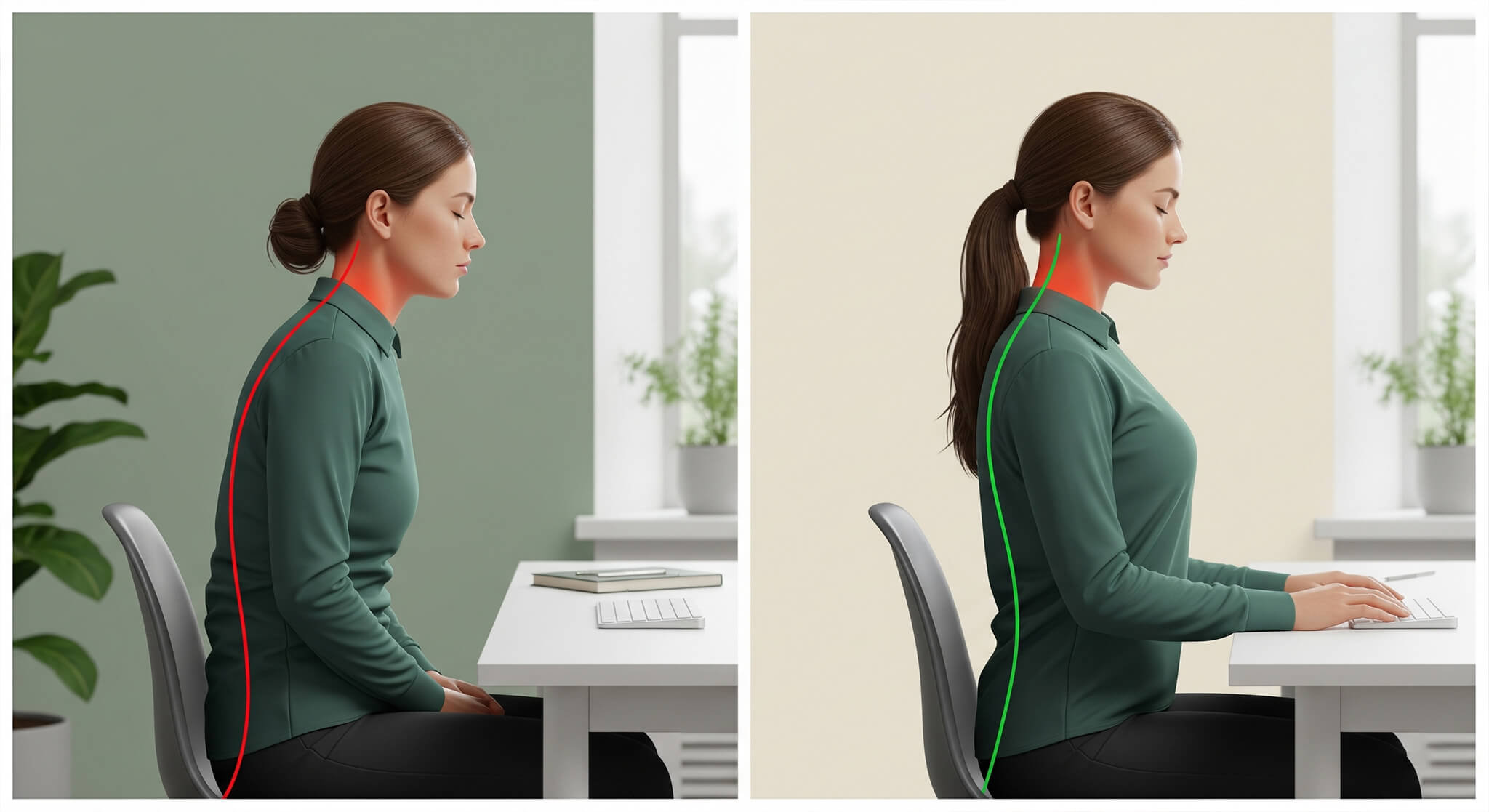

Sitting Alignment

Maintaining proper spinal curvature while seated is essential:

- Maintain a lumbar curve similar to standing.

- Back should be straight, shoulders back, bottom touching the back of the chair.

- Knees bent at 90 degrees, level with hips, feet flat on the floor or a footrest.

- Head retracted (chin tucked) to counter forward head posture.

I.B. Static vs. Dynamic Postural Control: Functional Assessment

Clinical assessment must distinguish between static control (holding a fixed position) and dynamic control (maintaining balance during movement).

- Static balance involves minimizing sway while holding a posture. However, clinical measures like the Balance Error Scoring System (BESS) often show limited reliability, suggesting static assessment alone provides only a partial view.

- Dynamic postural control refers to the body’s coordinated response to shifts in the center of mass, reflecting real-world resilience. Assessments like the modified Star Excursion Balance Test (SEBT) show better reliability. Dynamic assessment offers a superior measure of functional capacity and injury risk.

I.C. Defining and Classifying Postural Deviations

Postural deviations involve predictable changes in spinal curves and pelvic position.

- Forward Head Posture (FHP) and Thoracic Kyphosis: Increased upper back curve, rounded shoulders, depressed chest, and forward head with neck hyperextension. Often linked to reduced upper trapezius tone and pain around the shoulder blades.

- Lumbar Lordosis (Hyper-lordosis): Excessive lower back curve, associated with increased anterior pelvic tilt.

- Sway Back Posture: Decreased lower back curve, increased posterior pelvic tilt, and increased upper back curve (kyphosis). Reduces muscle contraction, increasing passive stress on the lumbar skeleton.

I.D. Clinical Controversy: The Anterior Pelvic Tilt (APT)

APT is often framed as a pathological misalignment causing low back pain. However, systematic reviews indicate APT is extremely common, even in pain-free populations (present in 85% of men and 75% of women in one study). Further reviews fail to establish a consensus causal link between specific postures like APT and low back pain.

The functional implication is that while APT may not directly cause pain, it profoundly influences movement. Excessive APT biases the body toward lumbar extension and limits pelvic and hip range of motion (restricting hip external rotation and full trunk flexion). This constrains efficient movement during gait, running, or squatting. The clinical objective is therefore not necessarily to "fix" the pelvic angle, but to restore the full range of necessary pelvic and hip movement options for functional resilience.

Table 1: Biomechanical Checklist for Optimal Posture (Standing and Sitting)

|

Postural Segment |

Standing Alignment Criterion |

Sitting Alignment Criterion |

Relevant Biomechanical Goal |

|

Feet & Base |

Weight evenly distributed, soft knees, feet flat on floor/footrest |

Feet flat, knees bent at 90 degrees, same level as hips [1, 7] |

Stable foundation, prevent joint locking, proper weight distribution |

|

Pelvis & Hips |

Neutral position, core engaged |

Bottom touching back of chair, hips/thighs supported and parallel to floor [5, 13] |

Maintain natural lumbar lordosis [1, 6] |

|

Torso & Spine |

Natural S-curve maintained, shoulders drawn back and down |

Back fully supported (lumbar support recommended), shoulders relaxed |

Minimize chronic strain on joints and ligaments |

|

Head & Neck |

Centered over shoulders, chin tucked (neutral) |

Head level, forward facing, monitor at or just below eye level [14] |

Reduce mechanical load associated with forward head posture |

II. Etiology and Pathophysiology of Postural Dysfunction in the Digital Age

Contemporary postural dysfunction is overwhelmingly driven by increased digital engagement and prolonged sedentary behavior.

II.A. The Sedentary Epidemic and Musculoskeletal Strain

Average screen time often reaches 6–10 hours daily. This extended static positioning, coupled with a lack of physical activity, directly contributes to musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) and chronic spinal pain. Habitual slouching and hunching cause shoulders to round and the head to protrude, disrupting muscle balance and imposing chronic stress on the cervical spine.

II.B. The High Cost of "Tech Neck" Syndrome (TNS)

The repeated neck flexion associated with mobile device use has resulted in "Text Neck Syndrome" (TNS). Prevalence of MSDs among smartphone users ranges from 50% to 84%, particularly affecting the neck, shoulders, and upper back. Risk factors include duration and frequency of improper positioning and lack of physical activity.

The detrimental effects extend beyond pain. A forward head and rounded shoulders compress the chest cavity, restricting deep breaths and impairing ventilation. This physiological consequence may contribute to hyperventilation, stress, and anxiety. Improved posture facilitates better ventilation, enhancing nervous system function.

II.C. Developmental Risks in Children and Adolescents

Extended screen time is strongly linked to back and neck pain in youth; one global review found every extra hour on a computer increased back pain risk by 8.2%. Over 70% of adolescents report postural problems related to screen time, sometimes starting by age 12.

Children are uniquely vulnerable as their musculoskeletal system is developing. A larger head-to-body ratio requires their neck muscles to work harder, leading to quicker fatigue. Constant neck flexion during this critical period (estimated 1,825 to 2,555 hours/year) places excess stress on the cervical spine.

This early stress can impair spinal development, leading to lifelong issues like premature disc narrowing, nerve root pressure, and persistent pain, fatigue, and even digestive issues from organ compression. Early intervention is crucial.

III. Comprehensive Health Benefits of Posture Correction

Improved posture provides systemic benefits beyond aesthetics or localized pain relief.

III.A. Musculoskeletal Longevity and Stability

Maintaining proper alignment minimizes chronic mechanical stress on bones, joints, and ligaments. It facilitates appropriate muscle use, allowing freer movement and longer engagement in activities. Correct posture naturally engages and strengthens crucial core musculature, stabilizing the spine and providing a robust foundation for movement, reducing the risk of falls and injuries later in life.

III.B. Systemic Physiological Enhancement

Good posture is inextricably linked to vital functions. A straight spine and open chest allow for deeper, more efficient breaths, increasing oxygen intake and reducing stress. Preventing the organ compression associated with slouching enhances gastrointestinal function, nutrient absorption, and waste elimination.

III.C. Psychological and Energy Outcomes

Better ventilation is associated with improved nervous system function, leading to a tangible boost in mood and energy levels. Standing and sitting tall has also been shown to enhance confidence and self-esteem.

IV. Ergonomic and Lifestyle Interventions

Lasting correction relies on effective ergonomic practices and consistent movement.

IV.A. Mastering the Workstation: Detailed Ergonomic Standards

Workstation design should support a neutral posture.

Sitting and Device Setup

- Back fully supported (lumbar support ideal).

- Head level, balanced over torso.

- Shoulders relaxed, upper arms hanging normally.

- Elbows close to body, bent 90-120 degrees; hands, wrists, forearms straight and parallel to floor.

- Monitor directly in front, arm's length away; top bar at or just below eye level.

- Keyboard and mouse at elbow height.

- Use caution with laptops due to low screen height.

Dynamic Work Practices

Avoid remaining still for prolonged periods. Movement is the most effective medicine for the spine.

- Alternate between sitting and standing every 20-60 minutes.

- Make small adjustments to chair/backrest.

- Take periodic breaks to stretch.

- Use a headset for phone calls to prevent neck twisting.

IV.B. Positional Strategy for Recovery and Maintenance

Lifting

Maintain the natural back curve; movement should originate from hips, knees, and thighs, not the back.

Sleeping Posture

- Best: Sleeping on the back evenly distributes weight. Place a pillow under the knees for better alignment.

- Good: Side sleeping, with a pillow placed between the knees to maintain hip and pelvic alignment.

- Avoid: Sleeping on the stomach applies the most pressure to the spine, forcing neck rotation.

V. Clinical and Active Corrective Strategies

Targeted rehabilitation is necessary to reverse existing postural dysfunction.

V.A. Evidence-Based Exercise Protocols for Muscular Imbalances

Correction requires strengthening weak, elongated muscles and stretching tight, shortened muscles.

- For Forward Head Posture & Rounded Shoulders: Stretch tight pectorals (Chest Doorway Stretch). Strengthen weak scapular stabilizers (Prone I, T, Y exercises – shown to provide superior improvement compared to stretching alone). Activate deep neck flexors (Chin Tucks).

- For Lumbar Lordosis: Strengthen abdominals and hip extensors (hamstrings, glutes). Stretch tight hip flexors and lumbar extensors.

- For Sway Back: Stretch shortened hamstrings and lumbar extensors. Strengthen hip flexors, upper-back extensors, and obliques.

- General Spinal Flexibility: Cat and Cow Pose.

Table 2: Common Postural Deviations, Associated Imbalances, and Corrective Focus

|

Postural Deviation |

Spinal Characteristic |

Likely Tight Muscles (Stretching Priority) |

Likely Weak Muscles (Strengthening Priority) |

Corrective Exercise Example |

|

Forward Head Posture (FHP) & Rounded Shoulders (RS) |

Increased posterior thoracic curve (Kyphosis) |

Pectorals, Upper Trapezius, Neck Extensors |

Scapular Stabilizers (Rhomboids, Mid/Lower Traps), Deep Neck Flexors |

Chest Doorway Stretch, Prone I, T, Y [27] |

|

Lordosis (Hyper-lordosis) |

Increased anterior lumbar curve, pelvic anterior tilt |

Hip Flexors, Lumbar Extensors |

Abdominals (Core), Hip Extensors (Hamstrings, Gluteals) |

Hamstring Stretch, Strengthening Obliques |

|

Sway Back |

Decreased anterior lumbar curve, increased thoracic curve |

Hamstrings, Lumbar Extensors |

Hip Flexors, Upper-Back Extensors, Obliques |

Chest Stretches, Lumbar Stability Exercises |

V.B. Professional Guidance: Physical Therapy vs. Chiropractic Care

- Physical Therapy (PT): Customized assessment and treatment focusing on strengthening, stretching, manual therapy, and joint mobilization to restore functional movement and retrain alignment.

- Chiropractic Care (CC): Focuses on spinal alignment through adjustments, complemented by exercise, stretches, and lifestyle guidance.

Comparative studies suggest both PT and CC are effective and safe for managing chronic low back pain, yielding comparable outcomes with no serious adverse events reported. Manual therapy (often integrated into PT or CC) may show superiority in short-term functional enhancement compared to purely exercise-based programs.

V.C. Technology in Posture Correction: Passive vs. Active Training

Wearable devices fall into two categories:

Passive Supports and the Risk of Dependency

Passive correctors (braces, garments) use bands to mechanically align the shoulders and spine. While they may offer temporary pain relief, evidence for long-term effectiveness is limited. A critical concern is the risk of muscle atrophy and dependency. These devices act as a crutch, bypassing the root cause (muscle weakness). Prolonged use can lead to decreased muscle activation and potential weakening, with users often reverting to poor posture once the device is removed.

Active Biofeedback Trainers

Smart posture correctors (e.g., Upright Go) use real-time biofeedback (gentle vibrations) to alert the user when slouching, compelling active self-correction. This active training produces faster, more sustainable results. Studies show significantly greater improvement in alignment (71% in 14 days) compared to passive braces (23% in 14 days). Biofeedback training is linked to better outcomes in reducing pain and improving muscle activation without creating dependency.

Table 3: Comparative Efficacy of Posture Correction Modalities

|

Modality |

Mechanism of Action |

Primary Benefits |

Critical Limitation / Risk |

Evidence Profile |

|

Passive Posture Braces |

External mechanical support |

Temporary pain relief, initial awareness |

Muscle atrophy, dependency, no sustainable strength gain |

Limited/Inconclusive for long-term |

|

Active Biofeedback Devices |

Real-time sensor feedback for active muscle training |

Active muscle training, superior alignment improvement, no dependency risk |

Higher initial cost, requires user engagement |

Moderate (Superior outcomes vs. passive bracing) |

|

Professional Therapy (PT/CC) |

Custom assessment, manual therapy, targeted exercises |

Restores functional movement, lasting correction, reduces chronic pain |

Requires consistency and adherence; higher long-term cost |

Strong (Gold standard for functional restoration) |

VI. Integrated Framework for Long-Term Postural Health

Sustainable correction requires integrating awareness, movement, and strengthening.

VI.A. The Paradigm Shift: From Static Fix to Dynamic Health

Effective management involves shifting from focusing on an ideal static position to maintaining dynamic awareness throughout the day. Gradually break ingrained habits using mindfulness techniques (e.g., imagining a string pulling you tall). Integrate lifestyle factors: regular exercise, adequate nutrition, quality sleep, and, most importantly, continuous movement and frequent position changes.

VI.B. Prioritizing Pediatric and Preventative Measures

Preventative measures in youth are paramount due to the high risk of musculoskeletal impairment from screen time. Parents and educators must watch for signs like persistent neck pain or headaches. Encourage children to hold devices higher and to stretch, change positions, and move frequently.

VI.C. Conclusion: Posture as a Key Determinant of Systemic Wellness

Postural health is a fundamental, multi-system determinant of overall well-being. Optimal alignment reduces stress on joints, strengthens core stability, enhances respiratory efficiency, improves digestion, boosts energy, and improves mood. Moving away from passive supports toward active, exercise-based training and technological biofeedback provides the most robust path toward sustainable musculoskeletal resilience.

References

- Rush University Medical Center:The Power of Good Posture

- Mayo Clinic:Office ergonomics: Your how-to guide

- Sylvaia.com :The Ultimate Guide to Relieving Back & Neck Pain